This section introduces the HARMS Program as a system to make urine drug testing (UDT) practical in your clinical setting. Whether you are already systematically applying UDT in your patients prescribed opioids for chronic pain, or are simply considering it, this is an overview to help you plan and refine your course. The waters of UDT are at-times cloudy, and we are hopeful others can learn from our successes and failures.

April 30, 2020

Welcome to the HARMS Program Manual! This manual is the culmination of 5+ years of work designing, implementing, studying and refining a clinic-wide system to make urine drug testing (UDT) practical in primary care. Although developed for use in patients with chronic pain prescribed opioids, many of the same UDT principles can be applied to patients prescribed opioids to treat opioid addiction (opioid agonist therapy such as methadone or buprenorphine/naloxone). We hope others will be able to learn from our successes and initial failures as they consider incorporating regular UDT into their clinical practice. As frontline clinicians practicing in a resource-limited setting, we are confident that the innovations developed here offer a practical approach that can be replicated in other clinical settings. We are hopeful they can be applied to lessen the suffering of patients suffering with chronic pain, addiction, and the many people lying on that grey area in between.

It is critical to highlight that the goal of urine drug testing is not to “catch” patients or to punish them. The most important thing to remember from this manual is that the goal of urine drug testing is simply to inform the risk/benefit balance for a given patient when prescribing opioids. This overriding principle guides the answers to questions about what to do if a patient does not provide a UDT; has an expected result; has an aberrant result that is anywhere from mild to major, a single concern or repeated concerns; and the innumerable other questions that may arise as you start applying UDT. The clinical Gestalt is critical, and UDT simply informs that clinical Gestalt. With the informed clinical Gestalt, open discussions conducted in a non-judgemental and non-punitive manner can be facilitated with the patient.

For the sake of completeness, let us start with describing why and how the HARMS Program came to be. As frontline family physicians, we were all too aware of the near-impossible task assigned to us for patients suffering with chronic pain – we are expected to manage their chronic pain effectively (with opioids being one of the limited tools in our toolbox), while not causing or enabling opioid addiction or misuse (two of the known risks of these medications). While every clinical decision comes down to balancing the risks and benefits, what makes opioids in chronic pain particularly challenging is that this risk/benefit assessment is inherently limited. Pain is a significant part of the assessment, and because there is no objective test for pain, we are reliant on self-reports. People who are being harmed by these medications (addiction and/or other misuse) happen to be exactly the people who often don’t want us to stop prescribing them. For example, if a patient prescribed opioids for chronic non-cancer pain (CNCP) is addicted he may be unwilling to disclose incriminating information for fear of having his prescription stopped and/or even being discharged from one’s practice. If someone is selling his opioid medications or trading them for other drugs then he too is inclined to want the opioid prescription to continue. There are few places in clinical medicine where the goals of the patient are potentially so harmful, and so discordant with the goals of the prescribing physician. This is not to say that the patient’s self-reported pain is not helpful, only that it does have significant limitations. This limitation necessitates the inclusion of other variables in our risk/benefit analysis of opioids, so that our management and monitoring are as informed and objective as possible.

While we will never have a perfect assessment of potential risks and benefits with opioids in CNCP, UDT offers on objective marker of risk that contributes to a more informed risk/benefit analysis. Patients with substance use disorders are at higher risk for opioid addiction, overdose and death (Busse 2017).

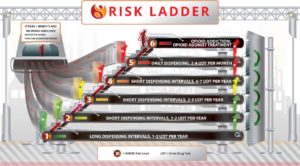

UDT is a central component of safe prescribing with opioid agonist treatment for opioid use disorder (methadone, or buprenorphine/naloxone). Essentially, UDT is a marker of clinical stability that is used to inform the risk/benefit balance of prescribing take-home doses. If someone prescribed methadone for example is actively using non-prescribed opioids, or cocaine, this suggests less clinical stability than an otherwise similar person (social status, mental health comorbidities, etc.) who is not using these drugs. That patient demonstrating clinical instability may then have take-home doses reduced and/or urine drug testing frequency increased.

Given that UDT informs risk/benefit balance when prescribing opioids to treat addiction, we might ask why it can’t also be used to inform the risk/benefit balance for patients prescribed opioids for CNCP? If someone with CNCP has a concerning UDT result, then does this too not tilt the risk/benefit balance and change if and how opioids are prescribed and further monitored? Numerous guidelines recommend UDT in patients with CNCP prescribed opioids (Gourlay 2005, Katz 2003, Dowell 2016), given its capacity to improve the way opioids are prescribed and/or further monitored for CNCP. However, it has not been widely adopted (Boulanger 2007, Bhamb 2006, Adams 2001). There are numerous reasons for UDT not being widely and effectively implemented into frontline clinical medicine for CNCP (Bair 2010, Kirsh 2015, Reisfield 2007, Starrels 2012).

Prior to starting what would become the HARMS Program, we were well aware of these barriers through our own clinical experience. While we had numerous case examples where we conducted UDT and it drastically changed our understanding of a patient’s risk/benefit balance and subsequent management – it was being applied sporadically, heterogeneously and with numerous obstacles. We didn’t know who to subject to UDT and how often, nor did we have a way of keeping track of who has been doing his/her required UDT and who hasn’t. We didn’t know where to conduct the UDT (clinic or lab); which type of UDT to use (immunoassay and/or confirmatory testing with liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry); or how to act on the spectrum of results (minor aberrancy to major, no-shows, etc.). We also had early experiences in which we misinterpreted UDT results, and subsequently had uninformed discussions with patients. We were not surprised to learn that encountering all of these barriers was not unique to our clinic – in fact they’re well-documented in the literature. We were also not the first to consider building a system to support routine UDT – “Healthcare systems and individual practices will need to be redesigned to support routine UDT” (Bair and Krebs 2010). However, as far we are aware, we are the first to initiate actually building a complete system to support routine UDT.

Over the ensuing years, numerous innovations were developed to address these UDT barriers, in what would collectively become a system known as the HARMS Program (High-yield Approach to Risk Mitigation and Safety). Given that HARMS was built in rural northern Ontario – where human and financial resources are limited – it has the potential to be easily expanded to other clinical settings.

Before giving an overview of how this UDT system (HARMS) works, it is important to acknowledge some UDT caveats. As mentioned, unfortunately UDT has occasionally taken on a punitive quality. That is completely against the intent of the HARMS Program. The HARMS Program aims to use UDT systematically to inform the risk/benefit balance of opioids, and if risks exceed benefits then the patient is supported while management is modified. Stopping the opioid prescription (even with an appropriately slow taper), without supporting the person, can prove detrimental to the patient and must be avoided. UDT is simply a tool to inform our risk/benefit balance when deciding about if and how to prescribe these medications. UDT informs the clinical picture but is not meant to be a replacement for good clinical judgement. There are many other factors that contribute to the risk/benefit balance and these need to be included in treatment decisions. In addition, especially with point-of-care (immunoassay) testing, there exists the possibility of false positives and negatives. It is important to know the limitations of testing prior to discussing with the patient and acting on results. The START-IT Tool (see Chapter 7) is a helpful way of attaining clinically meaningful feedback for any given IA result, including test limitations (false positives/negatives, etc.) and customized explanations. If you’re still not sure about what a result means, consider asking an expert in the area. The clinical biochemist at the lab can be very helpful for explaining the meaning and limitations of confirmatory testing (LC-MS). Even after applying UDT for >5 years now, we still have questions that arise and always find the clinical biochemist helpful.

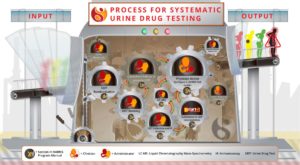

The HARMS Program (UDT System) is applied to all patients prescribed opioids for CNCP at our clinic with few exceptions – see Chapter 1. Once a patient is identified as being prescribed opioids for CNCP, the next step upon entering HARMS is estimation of risk, which will then guide how the UDT system is applied. The physician then notifies the clinical administrator (a designated, non-medical member of the clinic staff such as a secretary) of risk estimate, and the patient is added to a master list. Administration then randomly selects patients off of that master list at a rate concordant with risk – higher risk patients are subjected to more frequent UDT than lower risk patients. Once selected, the patient is called and booked for a UDT at the clinic. At our clinic, the UDT is conducted with a clinical employee who has no formal medical training. This was done to preserve precious nursing resources. The START-IT tool is applied at the UDT appointment to simplify the whole process of conducting a UDT on-site. START-IT utilizes a tablet PC to collect all of the information required for the test, including the immunoassay (“point-of-care”) UDT result. The START-IT interpretation is then uploaded into the electronic medical record (EMR) with the click of a button. If the result is unexpected, then the physician is notified of the result immediately. As applicable, the sample is then sent to the lab for confirmatory testing. If a patient is not providing a UDT despite repeated attempts, then the physician is notified of this as well. With the UDT results (or lack thereof) and any other new piece of information informing the clinical Gestalt, the physician can then consider altering prescribing and monitoring strategies accordingly. If risk level is changed or opioids are tapered and stopped, administration is notified and updates the master list.

The process is iterative, with each pass through the system providing more information about a given patient. If concerns are identified, then monitoring is tightened to hone in on the most accurate assessment we can get of substance use and risk/benefit balance.

To summarize the main innovations of HARMS and how they address previous UDT barriers:

- The HARMS Risk Ladder (Figure 3) was created to be an intuitive and versatile approach for not only determining how often to conduct UDT for a given risk level, but also how to adapt to the full spectrum of results (from minor concern to major). It takes principles for risk mitigation and safety used in opioid agonist treatment for addiction, and applies them to opioid-prescribing in CNCP.

- START-IT (Figure 4) is a one-stop shop for UDT in the office, as mentioned above. It collects all of the required information for a UDT and interprets it within the limitations of the test. The report is uploaded into the EMR with the click of a button. This is an important step in both reducing workload, and more important ensuring accuracy in the interpretation of UDT results. The literature has shown that physicians are not adept at interpretation of UDT and can even make disastrous mismanagement decisions based on these erroneous interpretations (Reisfield 2007, Starrels 2012, Christo 2011). Automated interpretation helps address this barrier.

All of this is well and good, but does such a system actually work? We conducted a retrospective chart review of all patients in our program who were not already identified as high-risk, and followed them for a 12-month period. What we found was that 19% (15/77) of patients had UDT results that directly changed management (starting opioid agonist treatment for addiction, escalation to a high-risk stream, or in a minority of cases tapering and discontinuing opioid medication) (Shahi and Patchett-Marble, Journal of Opioid Management 2020).

Since that study, numerous modifications have been made including the creation of more risk categories; changing the method of randomization from 10% per month for low risk patients to 1-2 tests per year; creation of a “recall list”; upgrades to START-IT including analyzing more panels and giving more customized information about what results mean and when to send for confirmatory testing. Now that HARMS has been created, studied, and refined it is ready for clinical expansion and more rigorous evaluation. Recent efforts have been focused on packaging for clinical dissemination with the creation of professional infographics, a website, a smartphone app and this manual.

If you are interested in participating in the evaluation of HARMS through becoming a pilot site, then please let us know. START-IT has been built to easily collect data (in addition to its other roles making UDT practical in the office).

As you review this manual and apply UDT to real-life patients, we would like to stress one more time that the intent is to inform the risk/benefit balance of opioids and guide if and how they should be prescribed and monitored. It is not the only marker. It is intended to complement the rest of the clinical Gestalt. This is the first edition of this manual and will continue to evolve in the next five years as it has over the last five. We appreciate you taking the time and energy to explore our system for urine drug testing,

Sincerely,

Dr. Ryan Patchett-Marble, MD, CCFP

HARMS Program Founder and Lead

Contact:

Case 1

You are a family physician with a full-scope of practice that includes chronic pain. You have dozens of patients in your practice that are prescribed opioids for chronic pain, and you feel uncomfortable about a number of them but can’t put your finger on why. Most of these patients you inherited from another physician who was quite liberal with the use of opioids in the CNCP population. You have done no regular monitoring in this population previously. You are interested in sorting out who might be benefitting with these medications and who might be harmed, so that you can adjust their treatment accordingly, but don’t know where to start. You consider validated patient questionnaires (ORT, SOAPP-R, DIRE, DAST, etc) to assess for general risk and addiction but don’t have time and have heard they’re not overly effective (“patients can lie”). On several occasions you have been very concerned about a patient and ordered a urine drug test, which provided concerning results and changed management, but it was a logistical hassle and you have no idea how you would apply this across your practice. What can you do to get started?

If this sounds like you, then you are in the right place! We are hopeful this manual can be helpful to you and act as a guide to applying a UDT system at any stage - from your initial consideration, to clinical implementation, to subsequent refinements unique to your own setting.